Over on the Society for Participatory Medicine mailing list we have been discussing the recent Readers Digest blog post titled: 50 things your nurse wont tell you.

You really have to read it before reading this article, this post will only make so much sense without that.

I suggested that part of being an epatient or a perhaps a cautious patient was being able to filter an article like this one as a “patient scientist”. E-patient Dave, as per normal, was not about to let me get away with just that, and asked “So, Fred, does that point (how to filter an article like this) become a P.M. teachable? And thus bloggable?”

So I figured I should take a moment and eat my own dog-food.

The first thing to note is that the role of the patient scientist is not an authoritative role. But the role of -any- scientist is not an authoritative role. Rather, it is the job of a scientist to be “carefully and productively dubious”. I believe that an engaged patient has an almost greater capacity to pursue this ideal than a doctor. One of a doctors roles is as a scientist, but only one of several roles. Another role for a doctor is to act as an authority, to posit a hypothesis rather than merely questioning. To put forward one particular idea and defend it with expertise and authority. But the patient has the privilege of merely questioning, without ever taking a stand on the idea in question. Ironically, this means that a patient can play the role of a scientist more completely than a doctor.

That might read like something as a contradiction but it isn’t as long as we clearly define science as “the process of productive questioning” and scientist as “the one who productively questions”. In the doctor patient relationship, the patient should be the “theory questioner” and the doctor the “theory maker”, which, in that brief moment, means that the patient is the one in the scientific role.

The irony ends here, of course, because while the doctor is in the “hypothesis making” role, the patient too often fails to properly take the “questioner” role. Further, the doctor is a trained scientist, so in reality the doctor is both putting forward a hypothesis, and also questioning it. Doctors who expose this internal dialogue are rarely paternalistic, because they expect the patient to understand that a diagnosis or a treatment plan are testable hypotheses. That can be pretty difficult for a patient to handle, but facing that uncertainty head-on is the central task of the e-patient. Extending this idea further, we can see that getting a second opinion is really just a special case of the scientific peer review process.

Being a patient scientist is a central part of being an engaged patient.

So how would a patient scientist read the list of 50 things your nurse wont tell you? Lets take a look. I will paraphrase the 50 points into statements that I can evaluate.

- if I say, ‘You have the right to a second opinion,’ that can be code for ‘I don’t like your doctor’

- sometimes the doctor won’t order enough pain medication.

- the stuff you tell us will probably get repeated (gossip)

- Gentler butt-wiping for nicer people.

- The nurse might not let you know she is worried.

- The nurse might not let you know that you are doing medically stupid things.

- If you’re happily texting and laughing I’m not going to believe that your pain is a ten out of ten

- The nurse assumes you are underestimating your use of drugs and alcohol.

- Nurses head off medical errors

- you can’t get admitted unless you’re really sick, and you’ll probably get sent home before you’re really ready

- nurses are overwhelmed by red-tape and charting

- hospitals are still filthy and full of drug-resistant germs.

- went to nursing school because I wanted to be a nurse, not because I wanted to be a doctor and didn’t make it.

- Grey’s Anatomy is not reality

- I’ll have a dying patient with horrible chest pain who says nothing, because he doesn’t want to bother me. But the guy with the infected toe…

- If you abuse the call button, you will get a reputation that can diminish the quality of your care later.

- You need to include herbals and other over the counter medications when you are asked about medications.

- This is a hospital and not a hotel

- This is a hospital and not a hotel

- The nurse might have test results but are waiting on a doctor

- When you ask me, ‘Have you ever done this before?’ I’ll always say yes. Even if I haven’t

- Nurses do not always help nurses

- Correcting difficult doctors is difficult creating opportunities for mistakes

- Doctors can be willing to blame nurses in a way that steals trust.

- If you would be willing to make a formal complaint when things go wrong, consider making a formal compliment when things go right.

- Nurses like to see long time patients return once they are healthy

- sometimes Nurses can make miracles happen

- Make sure you are not ignored when you say important information, even if the provider is looking at your chart.

- Never talk to a nurse while she’s getting your medications ready.

- Understand the chain of command for complaints and nursing is a demanding job

- If the person drawing your blood misses your vein the first time, ask for someone else.

- Never let your pain get out of control. Using a scale of zero to ten, with ten being the worst pain you can imagine, start asking for medication when your pain gets to a four. If you let it get really bad, it’s more difficult to get it under control. (one of the few that I did not summarize)

- Ask the nurse to wet your bandage or dressing before removal

- If you’re going to get blood drawn, drink two or three glasses of water beforehand. If you’re dehydrated, it’s a lot harder for us to find a vein, which means more poking with the needle

- Don’t hold your breath when you know we’re about to do something painful, like remove a tube or take the staples out of an incision. Doing that will just make it worse. Take a few deep breaths instead.

- don’t go into the hospital in July when the new residents start.

- Doctors don’t always tell you everything about your prognosis

- Have you washed your hands?

- Many doctors seem to have a lack of concern about pain. I’ve seen physicians perform very painful treatments without giving sedatives or pain medicine in advance, so the patient wakes up in agony.

- When you’re with someone who is dying, try to get in bed and snuggle with them. Often they feel very alone and just want to be touched. Many times my patients will tell me, ‘I’m living with cancer but dying from lack of affection’.

- warm the towels

- Sometimes desperate end-of-life measures are more torture than comfort.

- Husbands, listen to your wives if they tell you to go to the hospital.

- doctors diagnose but nurses heal

- If you do not understand what the doctor is telling you, say so

- know the next steps for your care.

- doctors help you understand whats wrong with you, nurses help you understand that you are still normal.

- don’t ask me out on a date.

- have a positive attitude

- say thank you.

First concept: Patients need Social Skills to get better care?

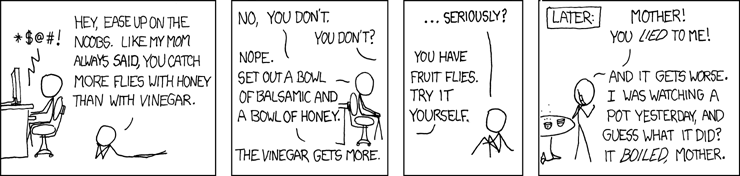

Ok, so first of all there are alot of things here fall into the category of “its better to be nice to your nurses” and/or “have the right attitude”. Specifically #4 , #15, #16, #18, #19, #25, #41, #48, #49, and #50 are all in this class. All of these are social skill issues. Of course, the recommended approach here is “You catch more flies with honey”, but that is probably not the right synthesis here. In fact that saying is a perfect example of a statement that does not bear scientific scrutiny.

In fact, real social skills does not mean “always be nice”. Social skills include how to complain effectively, how to confront without offending, and how to be gentle while still being insistent. Number 15 is a good example of this. The guy with the chest pain is not complaining enough, the guy with the toe pain is complaining too much. Social skills, at least for a patient, means knowing when being nice is not working, and something else is called for.

So now we have a statement that we can evaluate against evidence: “Do patients with better social skills get better care?”. Everyone who I talk to in medicine indicates that highly functional social skills are absolutely a predictor of good care. A quick review of PubMed shows that it will be difficult to search for something like this. Because searches on “social skills” usually return information about mental health. (i.e. social skills of psychiatric patients) but at least we have distilled a large portion of these points into something that A. we can evaluate scientifically (i.e. search for and consider published evidence) and B. we can engage with. We can discover if better patient social skills leads to better outcomes for patients and, if so, we can evaluate methods for improving our own social skills that might improve the quality of our care.

Part of a scientific consideration of a statement is to evaluate openly the biases of those who are creating statements. One bias is obvious here. This is the largest “grouping” that I could find in the “secrets from nurses” and it clearly shows a “appreciate us” bent. Perhaps, the frequency of this class of suggestion in the list is due to nurses feeling under-appreciated (a common problem) rather than its usefulness to patients. An “agenda” is a common bias in self-reported data. As patient scientists it is important to ferret out sources of bias in data we receive, especially from main stream media. All patient scientists should become comfortable with Wikipedia’s Bias category.

Pain management.

There were several comments regarding the mishandling of pain medication.

#2 suggested that doctors do not always order enough pain medication. #7 indicated that the nurse is going to be judging the validity of your pain reporting, and might find you unbelievable. #32 gives specific advice regarding controlling pain, specifically, that pain should be controlled before it really gets bad. #39 indicates that Doctors can be cavalier about pain.

All in all that is four entries on issues surrounding pain control, but with very divergent perspectives on the problem. It should be noted that at least two comments focus on the fact that doctors sometimes fail to effectively control pain. So is pain management a problem in hospitals? The evidence is easier to find here: The Joint Commission, an non-profit hospital accreditation organization, has made pain management part of its accreditation and education process. The joint commission is an evidence-based organization, which means that if it is focused on pain management, it is because it -is- a problem. I could dig deeper, into the research that the Joint Commission is using to drive its policies… but this is enough for now.

What is the take away lesson for e-patients?

If you are in so much pain that you cannot fall asleep, then your pain is not controlled. This rule applies even if you do not feel like you need to sleep right now. Its not about being tired, it is about anchoring your pain score around something objective. If I say “my pain is a 5” and you say “my pain is a 7” it is difficult to accurately compare those, or to determine from the number if the pain is under control. Whether or not you could fail asleep is a much much better measure. Too painful to sleep = too painful.

But understanding what pain levels are not tolerable is not enough. A patient must understand how to go about getting pain relief form the system. As the nurses suggest, sometimes the doctors simply do not care. Sometimes the ball gets dropped for other reasons, orders get shuffled, or medication orders do not go through. You might be suffering pain because someone has lost their sense of empathy, but it could be just as easily because a workflow is broken. As an e-patient, it should not matter why the pain is not being treated, you simply need to understand what you need to do to change the situation. Dr. Oliver has written lots about this, but the take-aways that I remember are.

- Someone needs to be keeping a journal of events in the hospital.

- This person should probably not be the patient. If you are in the hospital, you are probably so sick that you cannot discharge this responsibility yourself.

- Which is one of several reasons that patients should not be left in the hospital alone.

- The journal should include records of when pain medication is requested, as well as the time, medication name and dose when pain medication is delivered.

Pain control is something that Dr. Oliver writes about, which is where I am getting this short-hand advice. Dr. Oliver is my boss at the Cautious Patient Foundation and we regard failures in pain management as medical errors. As a result this is an area that I am concerned with as a technologist, and this is a core area that we educate about.

Conclusion

So I hope I have demonstrated, a little, how I think a patient scientist should react to anecdotes like the ones collected by Readers Digest. Treating them as “true” is a mistake, there are complex issues underneath, but it is possible to use them to start a critical thinking process that can lead to positive results.

I would also be interested in answering the following questions from the texts:

- “Is there evidence that patient reputations (i.e. between nursing shifts) can lead to poor care?”

- “What end of life issues are not typically being discussed by nurses? what damage can this cause to me as a patient?”

- “How tolerant should I be as an e-patient with poor blood drawing skills? Can proper hydration be used to address this problem?”

- “Are there higher medical error rates in July?”

All of these can be posed as a hypothesis, and approached scientifically by a patient.

I think it would be interesting to see some of these questions approached by other patient scientists. If you decide to blog about one of these, do send me a link.

-FT